CAMERA LENS PHOTO SLIPPED TUFT # 1

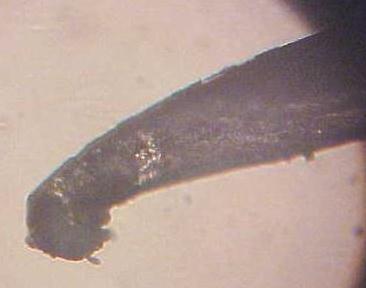

CAMERA LENS PHOTO SLIPPED TUFT # 2

Beyond the Senses page 2

Click here for page 1 here

Illustrated with Photos Taken Through the Lens

of a Microscope and Camera

An indepth study by Glen Conley

MICROSCOPE PHOTO PHYSICALLY BROKEN HOLLOW PORTION

By now you have probably figured out why deer hair can be so fragile and brittle.

The broken hair that you see was caused by improper, rough handling. A man stopped by with a buck in the back of the truck and asked if I would do the mount for him. I knew the guy and I knew that it wasn't his first day hunting or skinning, so I told him to skin it out down to the head and cut it off and I would take it from there. I was going to be going right past him in my evening routine and told him I would just swing in and pick it up on my way back in. I was running a little early, and when I got there he only had it skinned half way down the neck. I watched as he doubled up the skin at right angles to the hair and gave it a mighty pull. I volunteered to finish the skinning.

As soon as I got back with the cape, I laid it out flat on a table with the hair side out. Where he had pulled on the cape in the described fashion, a line as long as the width of two hands was evident. From that line came the pictured sample.

When you need to pull on a skin, fold it WITH the LAY of the HAIR. That is of course unless you like the instant moth-eaten look on your finished mounts.

You can get a little more of an idea of the inside diameter of the hollow portion of the hair. The dark shadow sections at the end of the break are the opposite side of the cylindrical wall.

The dark line separations around the hollow bubble structures are exterior pigments.

MICROSCOPE PHOTO DISSOLVED SHAFT # 1

At this point you have already got your eye balls trained to the point that you recognize this photo as the hollow portion of the hair, from the taper back.

"WHERE'S THE SHAFT???? It's gone. History. Ka-plooie. It ain't there no more!!!!"

Quit using the word ain't, ya sound like a red-neck. It's dissolved, just keep readin' and lookin'.

MICROSCOPE PHOTO DISSOLVED SHAFT # 2

"THERE'S THE SHAFT!!! BUT THAT AIN'T NO FOLLICLE!!!!"

I' ve already told you about the ain't word, and quit using double negatives, there's no tellin's who's reading this.

Try to contain your excitement of discovery a little better. I know it's hard, but it can be done.

You' re right that is not a follicle. This photo is another example of a dissolved shaft, only in this case only enough was dissolved at skin level to set up a slip condition. Now if you were to hold that hair up to the light and look at it with the naked eye, you would probably swear that was a follicle at the end of that shaft. Truly a different perspective when you can actually see what you are looking at.

The hair samples for both the DISSOLVED SHAFT photos came from the same deer.

From the stand-point of field care, the hunter had done every thing by the book as much as he possibly could. By state law, the deer is to be checked in with in 24 hours after it has been shot, and the head is to remain attached to the carcass until checked in. The deer was taken on a Sunday in the late afternoon. Check stations were closed, so he took off work early the next day in order to be in compliance. We skinned out the deer after formalities were out of the way, roughly 26 hours later. At that time the form of slipping that you just saw was taking place. Temperatures would not have exceeded 40 + degrees Farenheit on the high end.

The fastest time that I personally have seen this form of slip take place, and verify with microscopic exam, was 5 hours after the animal was killed. I have had reports of much shorter times than that, but I had no way to confirm, but were in all likelihood this form of slip.

Notice the hair with the pink circle appears to be almost straight. It is just simply on it's side.

The zig-zag shape is a "flat" shape as opposed to a spiral. Notice also that the follicle is gone as is the greater part of the shaft.

In the green circle, notice how the shaft has been curled back in a "J" shape, and that follicles are absent.

The "J" shape is always a give-away for the naked eye.

You will see in this sample that the hair has been dissolved all the way back into the hollow portion of the hair. This extreme form is the one that looks like as if the hair had been cut loose with scissors, but a bare patch of skin remains to be seen where the hair had been at.

SLIPPED TUFT photos # 1 and # 2 are samples from two different capes. The thing that they had in common was that they were both frozen raw, and the slippage happened after thawing.

I am now speculating that your head is now spinning with the deluge of new info and all the questions that go along with such an experience. Good. I hate being the only one with a spinning head. Can I answer all your questions? Probably not. But I might be able to answer a few.

If you came out of this article thinking in terms of , "The implications are that there is something other than bacteria that can cause hair slip", then the photos and text did their job. If not, one of us is going to have to go to the back of the class.

Many seek a simple one word answer for the cause of hair slip. Such an answer doesn't exist. The factors are many. All of the factors I have came up with to date promise to be the end results of some complex cycles. Diet alone being a big player. Expressed genetic traits, such as the zig-zag and straight hair examples used here indicate another group of players. Linked with that is expressed genetic traits in skin structure.

The dissolved hair form can also be induced chemically by unknowing accident. Some of my best leads have came from taxidermists that were having problems that provided me with sample specimens and detailed accounts of what they had done. Household products incorporated into an individual's "techniques" can be a wealth of antagonistic chemicals that act as catalysts. Some of the compounds introduced back into the quotient can be the very ones we seek to eliminate to begin with. To be thinking in terms of achieving a singular and desireable chemical reaction would be thinking wrong. The most likely thing to have set up would be a CHAIN of reactions.

The antelope hair pictured on the home page of TaxidermyReference.com is an example of incompatible compounds. It did not show up until the mount was drying out. I pointed out in the SLIPPED TUFT photos that the slipping occured after thawing. What's one got to do with the other?

The antelope hair like the deer hair is hollow. Stop and think about the insulating ability that that structure provides. In effect a "frost line" has been created than can allow evaporated off hydrogen and oxygen to condense as water. Water combines with caustic salts formed on the skin to produce a liquid caustic. Dissolved hair.

The SLIPPED TUFT hairs had frost form on the hairs while in the freezer. Frost melts, produces water, combines with salts, produces caustics, produces slip.

"But can't bacteria produce hair slippage?"

PHEW!!!!! Darn, you ask a lot of questions! Yeah. But not as quickly. Some where along the line in your education, you should have been exposed to a term, incubation period, in regards to bacteria as a disease pathogen. That incubation period term is also going to apply in the case of decomposing a skin. Since we are now going from hair to skin, we will save that one for the next installment. If you read this far, you've already got a lot to think about!

Related articles: